I’ve built tons of websites over the past eight years, all by hand, clacking out HTML and CSS into Notepad++ or BBEdit and then assembling it with AutoSite, usually. Despite playing with WYSIWYG editors throughout my life, I’ve just never liked them. Eventually, I just get frustrated enough with their lack of control, wonky markup, and strange workflows that I start writing markup by hand again anyway.

Of course, we all mellow out with age, and I not only had a fun opportunity to build another little site recently, but a CD-ROM image of Adobe PageMill 3.0 lying around to build it with. I found it rather adorable and enjoyable. Let’s talk about the brief history of PageMill, what sucks about it, and what fucks about it.

The lost art of the WYSIWYG site editor

A fun fact about the Web was that being able to easily build it was always part of the design spec. Tim Berners-Lee’s original WorldWideWeb browser had an editor component. Netscape Navigator became Netscape Communicator as it bloated from a simple browser to having the rest of the kitchen, including an editor named Composer, built in. While not officially part of Internet Explorer, Microsoft included FrontPage Express with just about everything they included IE with, Office getting the full fat FrontPage in some of its suites.

The problem with a lot of these WYSIWYG builders (“what you see is what you get”–say it like “wizzy-wig” because that’s fun) is that they often produce some really horrific markup. You see, the Web might’ve taken hold over Gopher because it was a more visual experience, but HTML originally had zero typesetting controls built into it. You as the user were meant to specify your preferred link, text, and background colors in your browser, and HTML was (and still is) solely meant for structuring the page into headers, paragraphs, and tables.

Over time, webmasters wanted more control, and the shitshow of presentational HTML, <font> tags for colors and sizes and the variety of ways to align and set margins on things, was born. This was such a mess to clean up that an entire DOCTYPE, HTML 4.0 Transitional, was established to let people both have the CSS setup they were supposed to be using and the <font>/<center>/etc. mess they were used to using. WYSIWYG editors used (often overused) presentational HTML at the user’s whims, making for pages that looked okay on the browser they were tuned for, but not on anyone else’s, and were nightmarish to debug and maintain. In my experience, FrontPage is probably the worst for it, but Composer and descendants have their share of answering to do.

Over time, as the Web became a lot less devil-may-care and the tools matured, editor markup settled down into acceptable status, right in time for the HTML standards themselves to bloat to obnoxious proportions. The audience for something like Composer or PageMill is now happy using drag-and-drop site builder stuff courtesy of Carrd or Squarespace (that was a joke, they just have Facebook pages now), and nerds like me are still writing out HTML tags in the text editors and IDEs of our choosing. I’ve had friends who literally work on servers for businesses all day tell me that being able to just conjure a page from markup is a weird, arcane, dark art, and at this point, I believe them.

Let’s step back to a time when that was less the case, though.

Ceneca sells out (the life and death of PageMill)

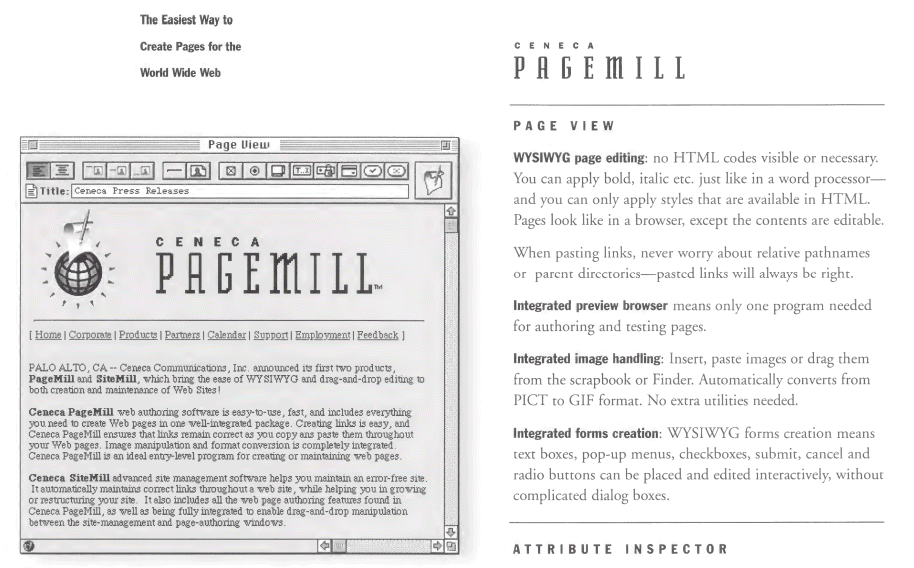

Adobe Systems Incorporated today announced it has signed a letter of intent to acquire Ceneca Communications, Inc., strengthening Adobe’s position as the leading vendor of professional-quality authoring tools for the Web. Ceneca is a privately-held developer of World Wide Web publishing and site management tools. […]

Last month Ceneca announced its new suite of Web authoring and site management tools that simplify the process of Web authoring. Ceneca PageMill™ makes creating Web pages as easy as producing a word-processed document, while Ceneca SiteMill™ dramatically simplifies site management. In the past, creating Web pages required an understanding of the details of HTML (Hypertext Mark-up Language), as well as knowledge of URL addresses and various image file formats. The Ceneca Web authoring products eliminate the need to understand all of the complexities of HTML, URL addresses and image file formats.

PageMill was the brainchild of a startup named Ceneca Communications, and I don’t know a lot about them other than that Adobe bought them. A lot of these editors were developed by smaller companies and then acquired by the big players looking to get even bigger, and once they were acquired, they didn’t have much of a reason to stick around. FrontPage was originally built by Vermeer Technologies and bought by Microsoft who saw it as part of their strategy to increase Internet Explorer lock-in (as FrontPage worked best with IE anyway). PageMill’s replacement, GoLive, was another Adobe acquisition, from a German-Californian company called GoNet.

PageMill started as a Mac-only program. Caby sometimes marvels about art teachers and tutors who are unaware of how much can be done on Windows these days, but a lot of really prominent desktop publishing and multimedia creation programs–PageMaker, Macromedia Director for you early Web game spergs and for us enhanced CD spergs, and both more Adobe acquisitions–started exclusive to the Macintosh. Even Microsoft Word, which started as a DOS program, didn’t really grow wings until the Mac versions heavily steered and influenced its interface. PageMill would come to Windows with version 2.0, but most of the nostalgia you’ll see for it comes from Mac users for a reason.

Adobe bought PageMill before it had even come out, and pre-release demos were apparently pretty positive:

If you tune into HTML-oriented chatter on the nets, you almost certainly have heard some of the excitement over Adobe shipping PageMill 1.0, the much-anticipated, graphically-oriented, Web page creation tool. Originally developed by the now-acquired Ceneca Communications, PageMill enables Web authors to create pages without working directly with HTML tags. The $99 PageMill lends itself to slick demos, and it nearly blew my socks off when I saw it last August at Boston Macworld.

TidBITS will review PageMill soon; in the meantime, the PageMill mailing list (monitored by people at Adobe) has had some discussions of good and bad features, with much of the concern focusing on PageMill’s lack of table support and its use of <br> tags when <p> tags would be more appropriate. People on the list have reported successfully purchasing the electronic version of PageMill from Adobe, though when you purchase the electronic version, you must have a fax number so Adobe can fax you a special URL, which you then use to download the program.

PageMill would get updated twice for emerging technologies, but 1995 to 2000 was about eighty years on the Web, and PageMill was never going to keep up. Those five years saw about an additional 300 million people coming online, the death of Netscape, IE winning the browser war, the emergence of Gecko (the layout engine that would power Firefox), the standardization of CSS, online commerce taking off, the hunger for what was then called “dynamic HTML” or DHTML, now just what we’d consider Web app behavior, and the codification of the blog, the wiki, and the forum as concepts. A simple little graphical page builder for laying out an HTML 3.2 page like a Word document wasn’t something people were going to pay for forever, and that was Adobe’s rationale behind its sunset:

Bergstrom said he feels consumers who simply wish to produce personal home pages will create them with the tools provided by other programs such as Microsoft Word or AppleWorks, and through online building tools such as Apple Computer Inc.’s HomePage, a component of its iTools services.

“Consumers want to share their memories online, show their pictures to friends, talk about their hobbies, that sort of thing,” Bergstrom said. “You may see consumer Web building tools offered as a bundle, but I really don’t see many being offered as shrink-wrapped solutions anymore.”

In comparison, GoLive integrated with Adobe’s other offerings, especially Photoshop, and was targeted more at the desktop publishing/paper design people who were moving into the Web space over the already savvy Web professionals that Dreamweaver were courting. GoLive itself would cease to be in the spring of 2008, and Dreamweaver survives to this day as SaaS subscription garbage like every other ulcer Adobe gives the world.

An opportunity presents itself

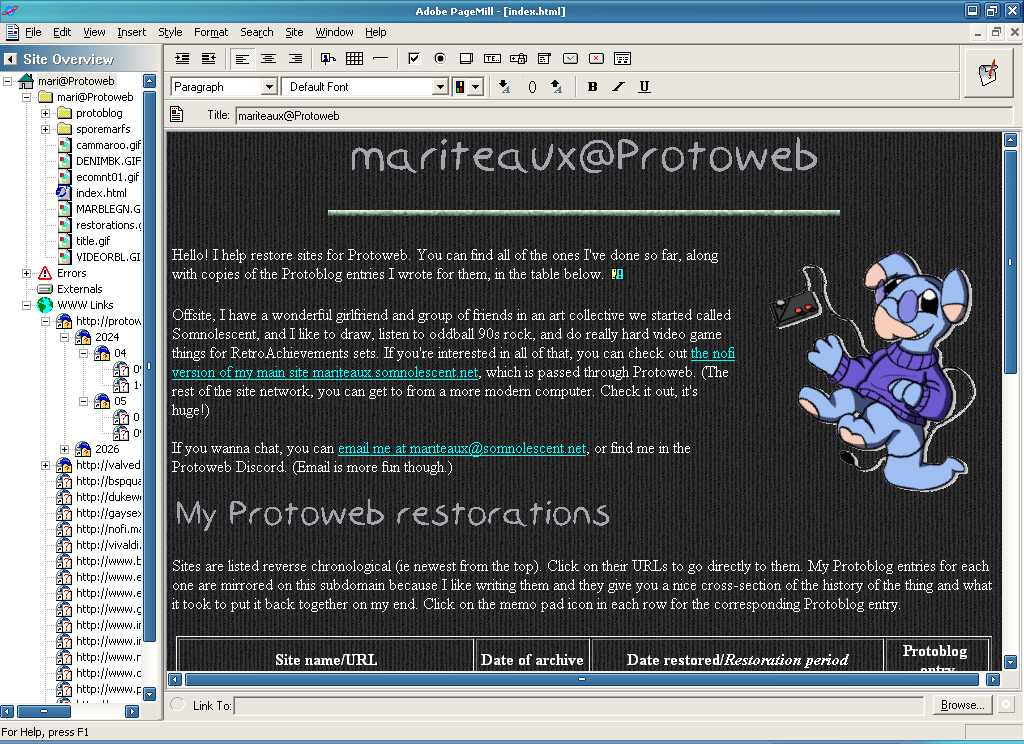

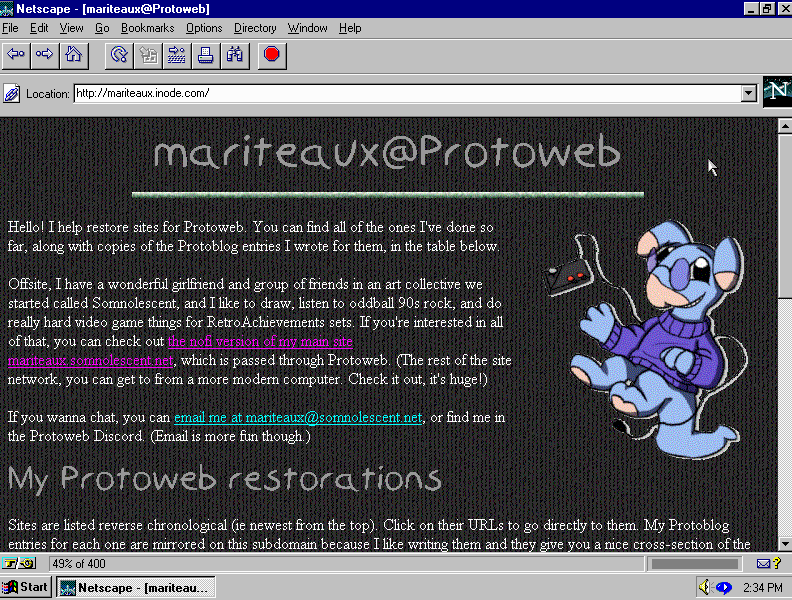

As much as I love a good wistful history lesson about the early Web, we have a site to build, so let’s go hands-on. I recently started contributing again to Protoweb, a living museum of restored early websites. One of the perks of being a contributor is that, if you request it, they’ll give you some hosting space and a subdomain or two under inode.com, which is where Protoweb’s site index lives, for whatever you’d want a Protoweb-exclusive site for. Originally, I was only interested in a subdomain for an idea I had to give people a peek behind the curtain, a blog series about the messy guts of what site restoration actually entails, but I was also given mariteaux.inode.com in the bargain.

Now, my proper website (specifically the nofi flavor) is already passed through Protoweb, and I don’t need another personal site anyway. That said, I saw a purpose for mariteaux.inode.com that nothing on Somnolescent could similarly serve–a “resume” of my restorations. You see, you can pull up my author page on the Protoblog to see which sites I’ve put back together, but the Protoblog isn’t accessible through Protoweb, and that page is kind of out of the way anyway. With a little portfolio site, all my work for Protoweb could be collected in one spot with direct links to those works, complete with the history lesson writeups I do to announce each new site on the Protoblog.

Around the same time, I was looking through my folder of random CD-ROM disc images and discovered I’d downloaded a copy of PageMill 3.0 at some point. My mission became clear: make this thing in PageMill, and have a lot of fun doing it.

Spinning up the PageMill (and what extra you get with it)

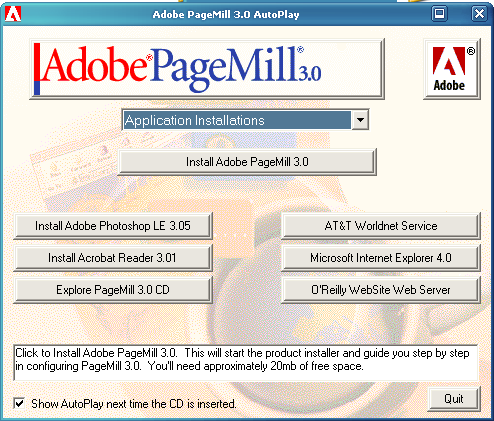

PageMill 3.0 is pretty typical to install. There’s a lot of optional extras on the CD-ROM, including Photoshop LE 3.05 (effectively a precursor to Photoshop Elements), Acrobat 3.01, Internet Explorer 4.0, O’Reilly WebSite Web Server, and the software needed to get on AT&T Worldnet, their competitor to AOL dial-up. These are all extras, thankfully, and PageMill can be installed without any of them. You will need a serial to complete the install, but those are as easy to find online as the software itself.

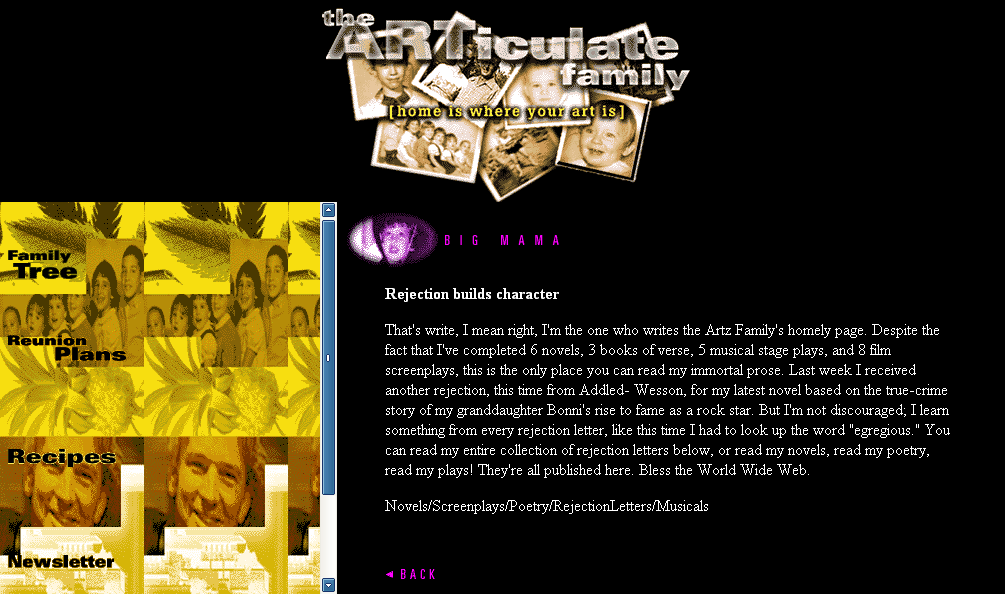

What I didn’t discover until I started to dig around for this blog post was that there’s actually quite a lot of sample material, graphics and even entire layouts, for you to use packed into the CD-ROM. The templates cover the whole range of personal, commercial, and communal uses for a website–photo albums, order sheets, restaurant menus, newsletters, conservation efforts, resumes, family sites–and y’know what, I really like these! They were definitely cooked up by an actual design team, but they’re surprisingly kooky and more than a little varied in aesthetic. I kinda wish some of these were real websites, frankly.

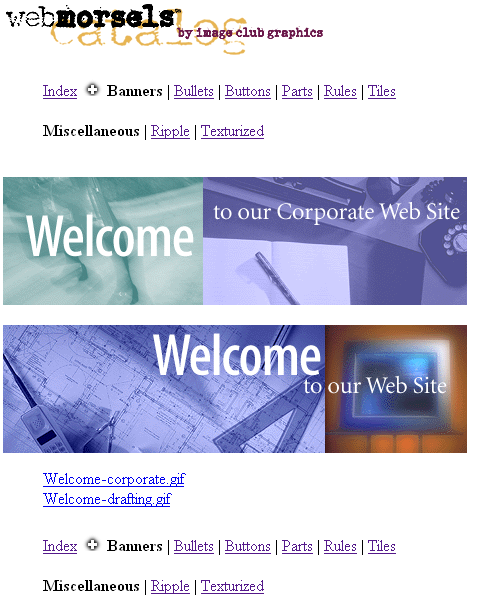

And of the graphics! I was happy with what I put together for my site, but man, once I saw the sheer 90sness of some of these backgrounds, buttons, and rules? It only felt right to start swapping things out and seeing what I liked better. I built it in PageMill! I have to use PageMill graphics for it. That’s Only Correct.

Apparently these were a sampler for a pack called WebMorsels Basic Bites, courtesy of Adobe Image Club Graphics–two things I can find precious little about online today! I suspect that means the pack was never officially released, and the samplers included with PageMill and Adobe WebType are all that became of them. (There is a text catalog on the CD-ROM advertising packs like PhotoGear, Circa:Art, which is an art history pack, and of course, WebMorsels, but basically all of these are nonexistent online today.)

Either way, I find WebMorsels highly delicious.

The build process

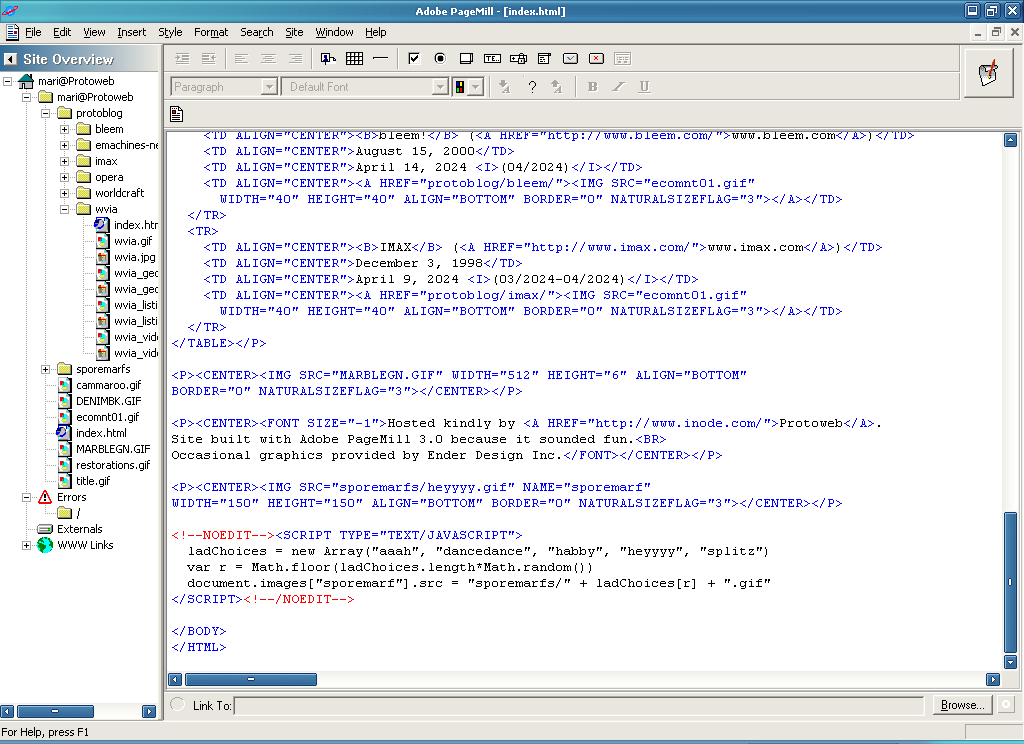

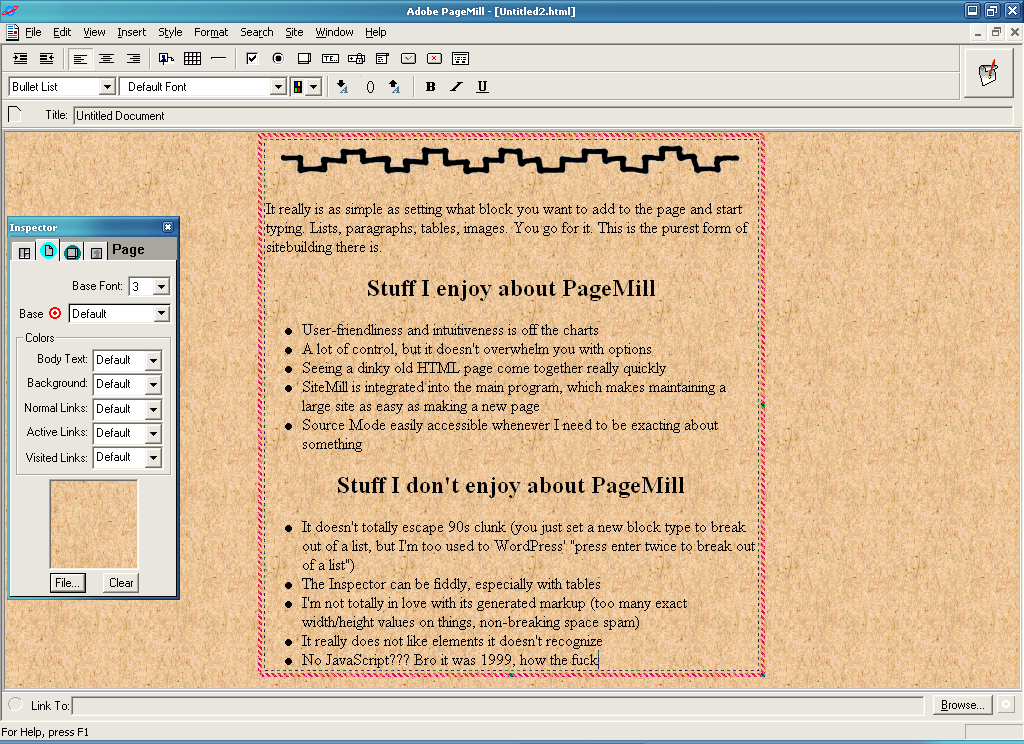

PageMill presents you with a blank page exactly like a word processor when you start. You get a few font, block type (paragraph, heading, bullet/numbered list, etc), and alignment options in two toolbars up top, plus a third for document title. Another toolbar at the bottom is for editing link destinations. Inserting images, ActiveX controls, form elements, and tables is done through the Insert menu, text styling the Style menu, and positioning the Format menu. It’s pretty intuitive, and you really don’t need a manual if you’re willing to spend five minutes clicking around, or have used a WYSIWYG editor in the past.

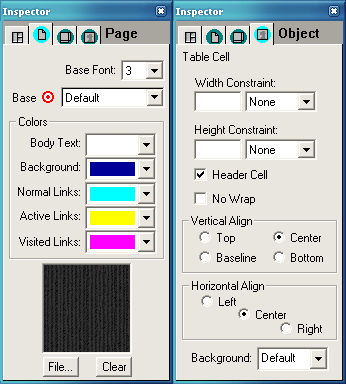

PageMill offers a floating window called the Inspector for setting certain properties on elements. This isn’t necessary for basic adjustments, only for when you’re really getting into the weeds of a complex element or the overall look of your page. Forms use the Inspector to set the action of the form, so where the form will submit its output to and what HTTP method it’ll use. You can set the width and height of many elements, including tables and table cells, horizontal rules, and images, through the Inspector. Your page’s colors and backgrounds are set through the Page tab of the Inspector.

Sometimes, telling PageMill exactly where you want to insert something can be fiddly, but what’s excellent is that at any moment, Ctrl+H brings up Source Mode so you can exact adjustments to your page markup as needed. Amusingly, PageMill uses HTML comments to mark where your cursor is on the page–can’t say I’ve ever seen that in an editor.

What I like about PageMill (and what I don’t)…

I really do like PageMill. It’s quick to learn and to get building a page, and the things you’d want to do on an HTML 3.2 page, like center-aligning headings, inserting horizontal rules and images and aligning them, and even building slightly more complex layouts using tables are incredibly easy to pull off, oftentimes one-click maneuvers. You can even quickly drop in <a> anchors for linking to parts of longer pages and clear <br>s right from the menu. That’s pretty handy. For the occasional moment where I edit my PageMill site externally (say, doing a Find in Files in Notepad++ to test out new backgrounds), PageMill will notice the changes and offer to reload its copy of the page. Slick.

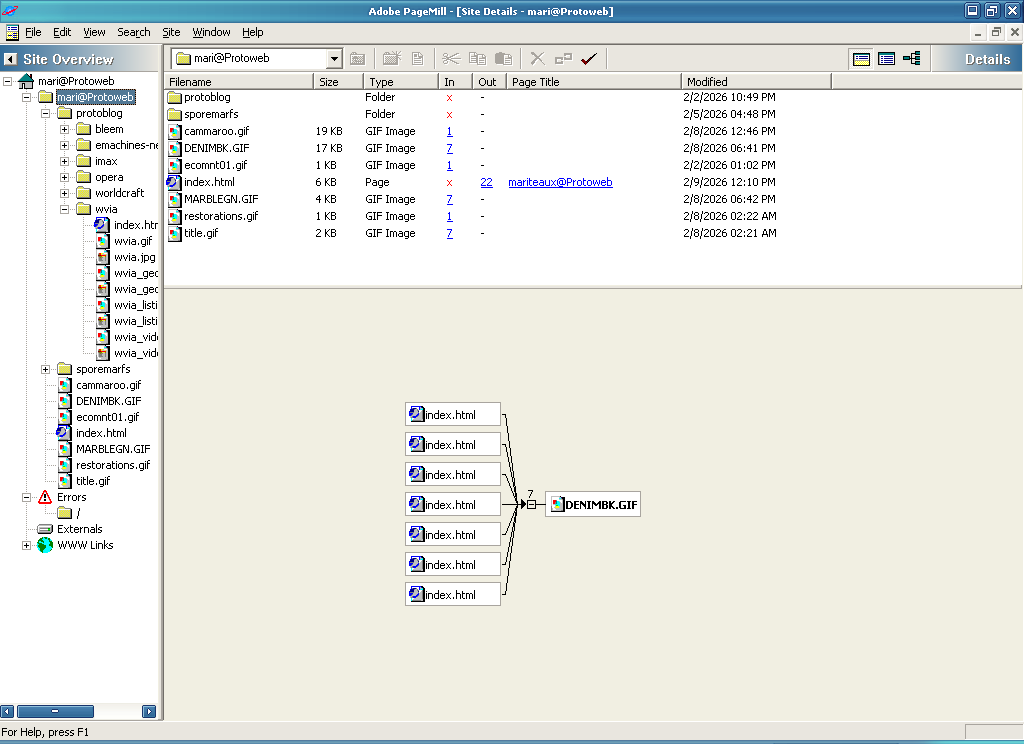

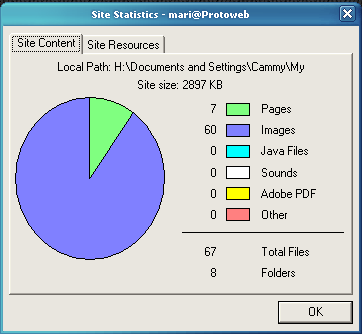

I’ve occasionally mentioned SiteMill alongside PageMill. SiteMill was the next step up from PageMill, simplifying the management of a group of pages and assets. It finds broken links for you, patches asset references when images move around, and gives you lots of statistics and numbers on where your site’s linking and how much space it takes up in all, important when you’ve only got 10MB on your Web host to work with. PageMill 3.0 integrates SiteMill functionality directly into it, letting you take your one page and build it out into a whole site really quickly. Granted, it is pretty basic stuff–and in one of the biggest oversights, it treats relative links like / and ../ as errors–but given PageMill can open multiple pages at once, it’d feel incomplete not to have a way to manage them all together. I’m glad to have it.

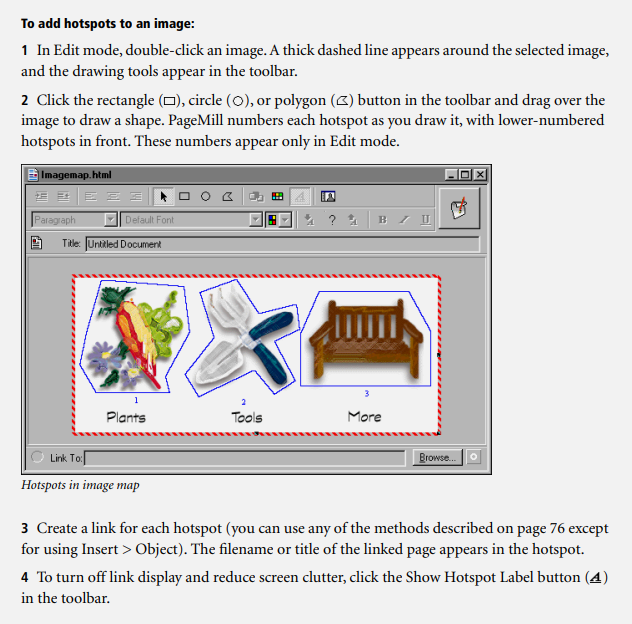

While I didn’t use it for this site, PageMill also features imagemap generating functionality! You can set an image to be a map and then draw out the clickable regions with your mouse. That’s hot stuff for a 90s website. Though imagemaps are still supported in modern browsers, they’re pretty well forgotten now, but back when layout possibilities were so limited, you could make a quirky, decorative navigation menu for your site in an image editor and then use PageMill to generate either the client-side or server-side imagemap code for it. I actually use a website tool for drawing imagemap regions for my more serious site projects, so the fact that PageMill just has it built in is kino.

PageMill isn’t perfect, however. No WYSIWYG editor could possibly be, but here’s some of the more egregious things I’ve noticed in making mariteaux.inode.com with it.

No JavaScript support?

Yeah, despite PageMill 3.0 having been released in 1999, there is zero support for embedding or referencing JavaScript in a page. You can embed ActiveX controls and Java applets into a page, but not plain-ass JavaScript like every website was using at this point. This is the single most bizarre oversight of the entire program to me.

In general, PageMill really doesn’t like elements it doesn’t recognize, treating them as errors and then encoding their tags as literal greater than and less than symbols on the page, destroying their functionality even for user agents that do support them. It seems Adobe was aware of the issue and created the not-immediately-obvious-what-it’s-for “placeholder” object as a workaround. This is a set of HTML comments (<!--NOEDIT--> and <!--/NOEDIT-->) that effectively let you hide things from PageMill. What’s between those comments, PageMill simply smiles and backs away from.

In their marketing material, Adobe described these as “elements allowing you to place literally any text, code, or image on your page”, though why PageMill needs such a thing when just not destroying things it doesn’t recognize seems easier is beyond me.

Inspector foibles

The Inspector is bit glitchy sometimes. As said, clicking on an object with more than meets the eye to set on it brings up the Inspector’s Object tab. This is simple enough with an image–click an image, you can set the width and height and alt text and a border and if it’s just an image or a full-blown imagemap–but then you get to tables and it misbehaves.

Tables have two different Inspector Object views, one for the whole table (for setting table size, cell padding and spacing, border values, and captions), and one for individual cells (again for sizing, spacing, and if that cell is a normal cell or a header cell). Actually getting the view you want to pop up is mostly an exercise in clicking in and out of the table until it registers properly. I also can’t make the Object view for images in tables pop up.

(Late-breaking update: I have read in the manual that if you simply click the table and then go to Edit > Table > Select More, it’s easy to go up and down the Object hierarchy and select what you want. This does seem to work alright, and when you’ve gotten a table cell selected, it’s a lot easier to select others, even if there’s not a great visual representation of that happening on screen. Can I still charge PageMill with acting not like I’d expect it to? Certainly, but at least there’s a workaround. Read your 90s software manuals, kids!)

Links are iffy if you don’t handle them right

Links are uncharacteristically clunky in PageMill at first. You highlight some text, right-click, and select “Make Link…”. This pulls up a Windows file open dialog that lets you link to something on your local drive. That’s not what you want, though, and I’m tempted to say in any situation. Even for local files, but especially for external links, pick the “Edit Link” option, which is a little confusing because there’s not actually a link there yet, but this will hop you down to the bottom toolbar for actually typing out where you want that link to go. Going through “Make Link…” like makes sense just confuses both you and PageMill. Not to go full Ben Shapiro on anybody, but Words Mean Things, y’know.

Tweaker markup

PageMill’s markup is definitely better than a lot of WYSIWYG editors. It tries to wrap stuff around 60 columns, but it’ll go for longer if it needs to. Tags are capitalized. PageMill credits itself in a <meta> tag, which I like as a Web archaeologist type. Paragraphs are properly closed (HTML doesn’t require a closing tag for paragraphs or list elements, but this helps avoid ambiguity). Presentational HTML mostly happens where you tell it to, and not wherever the editor feels like adding it.

Still, it’s not perfect–I’ve caught it trying to wrap images in <font> tags where I inserted an image while my cursor was in a heading element, despite trying to break to a new line with the Enter key beforehand, and it really spams up tables with non-breaking spaces and explicit height declarations. Thankfully, the Source Mode lets you clean this stuff up pretty quickly, and PageMill won’t try to readd it unless you go fucking around with the element some more.

If you’re a stickler for character encoding, also, PageMill 3.0 will recognize you setting a <meta> tag for UTF-8–and it will complain about it every time you go into Source Mode from then on. If you really don’t need to use Source Mode often, that might not be a dealbreaker for you (not that I imagine anyone who doesn’t giving a shit about character encodings), but it annoyed me enough into giving up setting a character encoding in the first place. In short, no UTF-8, we ride or die ISO-8859-1.

…And why I wish I had more to use it for

All of that’s stuff I can live with, though. I’ve really enjoyed my time with PageMill. I think I’ve finally found a WYSIWYG editor from the time I properly enjoy using. It’s slick, it’s effective, its output is relatively clean, the SiteMill functionality is simple but useful, and again, gripes aside, it really does feel like an HTML page builder that even average people can learn and use. It’s really no more complicated than Word, and arguably, PageMill’s advanced functionality is far easier to get to grips with than any of the mail merge and document style junk that’s been plaguing Word longer than I’ve been alive.

Obviously, there’s no Practical reason to use PageMill in 2026, but I’m tired of talking about practicality. I’ve been on about that for years. It’s old. Having a site in 2026 is impractical. Life is impractical. We’re here to have fun, and PageMill is damn fun to use.

As said above about JavaScript, you can do anything PageMill doesn’t directly support through use of a placeholder object. Conceivably, you could build a more modern website with HTML5 audio and video and CSS stylesheets using it, but you’d be putting in those tags by hand using Source Mode and giving up PageMill’s ability to preview the page accurately in the process, so that properly isn’t very practical. Doable, and new browsers will support it, but I don’t see much reason to mix the worlds. Enjoy your PageMill site for the eternal 1997 flavor it’ll have regardless of what you do.

Should you be connected to the Protoweb proxy on another device, you can see my PageMill creation, alongside the Cammy Blumaroo I drew for it, at mariteaux.inode.com. (If you’re not, you should get on Protoweb, it’s fun! But here’s a mirror on archives either way.) I’m thrilled with how it came out and how effortless the whole thing feels. I actually built the prototype of my little restoration storytime blog, what I went down this rabbit hole for in the first place, by hand, but now, I think I might rebuild and maintain it with PageMill. I really enjoy using it that much.

And this whole venture and writing this longass post about something only I’ve thought about this week gets me pondering doing the same for other HTML editors, everything from iWeb to HomeSite, in the future. I too really enjoyed writing it that much.